Andrew is a board member of Our Hearings, Our Voice; a group of young people who use their lived experience to push for change in the Children’s Hearings System. Part of this mission includes reaching out and influencing relevant professionals who work with children and young people withing the care sector. Andrew recently delivered an impactful presentation to education students at Strathclyde University to help develop their knowledge and awareness of their vital supportive role in Hearings-experienced children’s lives. In this blog, Andrew discusses some of the key messages he wishes to impart to professionals…

“One of the areas that I care deeply about in regard to improving the lives of young people going through the Children’s Hearings System, is their treatment from teachers and other educational staff. This is close to my heart due to some negative past experiences that I have had during my time in education. These experiences gave me the desire and fortitude to try and raise awareness of the changes that the system needs so badly.

I currently study History and Education at Strathclyde University with the goal of becoming a history teacher. During my first year I approached one of my lecturers after a class on the Children’s Hearings System and offered my experiences from the other side of the system to help expand my fellow students’ understanding.

My lecturer came back to me with the idea of creating a talk with a few of the other board members from OHOV to give to students currently studying education at Strathclyde. Whilst many of these students would be going into careers other than teaching, we felt that our message would be vital for them in their careers of working with children and young people.

The adults who work with us must learn not to judge the young people who they may see as acting out as they may have worse things going on in their private lives that is having a detrimental effect on them.

After I had this conversation, I approached the other board members of OHOV to see who would be interested in doing this talk and what messages we would want to convey to the students that we would be talking to. After much discussion we came away with six key themes that we felt were central to our message:

- Privacy

- Pastoral support

- Stigma

- High expectation

- Behaviour

- Labelling

Two of the other board members, Ash and Abbie, were interested in presenting with me at Strathclyde Uni. Ash, Abbie, and I wrote the presentation using our own experiences, and some quotes our fellow board members had shared with us. I’m going to share a little bit about the presentation we gave on the six themes above:

Privacy: Many of us value our privacy and only want those whom we trust to be told the details of our lives. Some of the young people on the OHOV board were ok with certain trusted staff knowing about our lives:

“I had one teacher that was really nice and she supported me in my hearings. If I ever had to go through it again, I would always pick her again and again” – Daniel

Other young people were less happy about it:

“My depute came to my hearing and found out all my personal information. That made me really uncomfortable.” – Claire

If teachers are given sensitive information about our circumstances, we would want them to treat this information as if it was their own, and resist the temptation to share it with colleagues. Our lives should never be staffroom gossip.

Pastoral support: If a child is attending Hearings or is in care, it’s usually because their needs are not being met at home. Life might be chaotic, uncertain, and overwhelming at times for us. It was clear in our meeting that some of our young people saw school as a safe place and something completely separate from home. They wanted to keep it that way and didn’t want to be treated any differently:

“I don’t want to be treated any differently just because I’m care experienced. I shouldn’t be given special treatment. I don’t want them to keep asking me if I’m feeling ok. That does my head in” – Lee

Some of us wanted our school to be aware of what was happening in our lives so they could support us:

“If we have attended a hearing that day, give us space and time to properly process everything before we start work. Ask if you can support us” – Ash

“My school had somewhere you could go to if you were having a hard time. That really helped” – Daniel

So how do teachers know what to do? Take a personalised approach. Ask if the child or young person needs additional support. If they don’t, then treat the child like any other pupil.

Stigma: The media often portrays us as victims, needing protection from abusive or irresponsible parents. They see us as a product of a broken care system. You only have to look at programmes like Tracy Beaker, or read some of the sensationalist newspaper headlines about children in care. We ask education staff to think about the way they speak about us and our families. Avoid sweeping generalisations and stereotypes that add to the stigma we already face.

High expectations: Teachers may have heard statistics before that have shaped their expectations of us, also society’s expectations of us. Like, in Scotland, 8% of looked after young people go straight from school to Higher Education compared with 41% of their peers. We want to remind professionals that care experienced people are individuals. We’re more than a statistic. If teachers’ expectations of us are low, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophesy and we are likely to perform poorly. This is called the Pygmalion Effect. There was an experiment done in 1968 by psychologists Rosenthal and Jacobson. They gave a class of pupils an aptitude test and told their teacher which pupils had performed the best. Unknown to the teacher, these tests were never even marked, and the group of ‘star’ children was chosen at random. At the end of the school year, the pupils were tested again. This time the papers were marked. The children who’d been described as gifted outperformed the rest of the children. This shows that teacher expectation can affect how children perform. Just because we are care experienced, we can still exceed at school:

“Don’t just expect children in care to not have many qualities. They might need your help to find their qualities” – Leanne

“Don’t be judgemental. Don’t disregard a young persons’ intelligence due to their circumstances” – Abbie

Many of the young people on the OHOV board have chosen to go on to further education. We’re proud of what we’ve achieved, but we don’t like hearing things like, ‘oh he’s doing really well, in spite of what she’s been through.’

Behaviour: The main message that we wanted to convey to everyone is that you must learn to be more understanding of us. Many children who are looked after might be experiencing difficulties in their lives. They might struggle to organise themselves and the things they need for school, or to get there on time. They might struggle to be there at all. If a child has a million things going on in their head and is dealing with the effects of trauma, making sure they have their gym kit might be the last thing on their mind:

“The fact I’m in your class is a victory. If I’m unprepared, speak to me privately” – Ash

Avoid being confrontational. Make your class a safe place. Try not to take it personally if a child is showing behaviour that you find challenging:

“Be sensitive to attitude and emotions. I can be a bit cheeky when I’m upset” – Penny

It’s clear from the above quote that the young person isn’t being cheeky because she doesn’t like the teacher, or wants to annoy them. It’s because she’s upset. That doesn’t make the behaviour ok, but shouting at a child who’s upset isn’t ok either.

Labelling: When teachers have a class full of children, we know that behaviour that disrupts teaching and learning can be difficult to deal with. When talking about this behaviour to children, or talking about children to colleagues, don’t judge or label children. Calling behaviour annoying, rude, or aggressive is just one person’s take on the behaviour. Describe exactly what the behaviour was: instead of ‘Jamie was angry and became violent so he took it out on his friend and started a fight with him for no reason’. Say ‘Jamie approached his friend and pushed him’. Stick to the facts, don’t label children or their behaviour. It’s really stigmatising.

In handover notes, or written reports staff shouldn’t pass over anything that’s not true or necessary. The child is doesn’t need a paper trail of judgements following them. If a teacher gets a pupil in her class and has been prewarned that he’s ‘difficult’ or ‘a nightmare’ she’ll inevitably see that behaviour in him because she’s expecting it. This is called confirmation bias.

Our message was well received by the classes that we presented to and many students said that our views and experiences helped them to broaden their understanding of their role in protecting and supporting hearings experienced children.

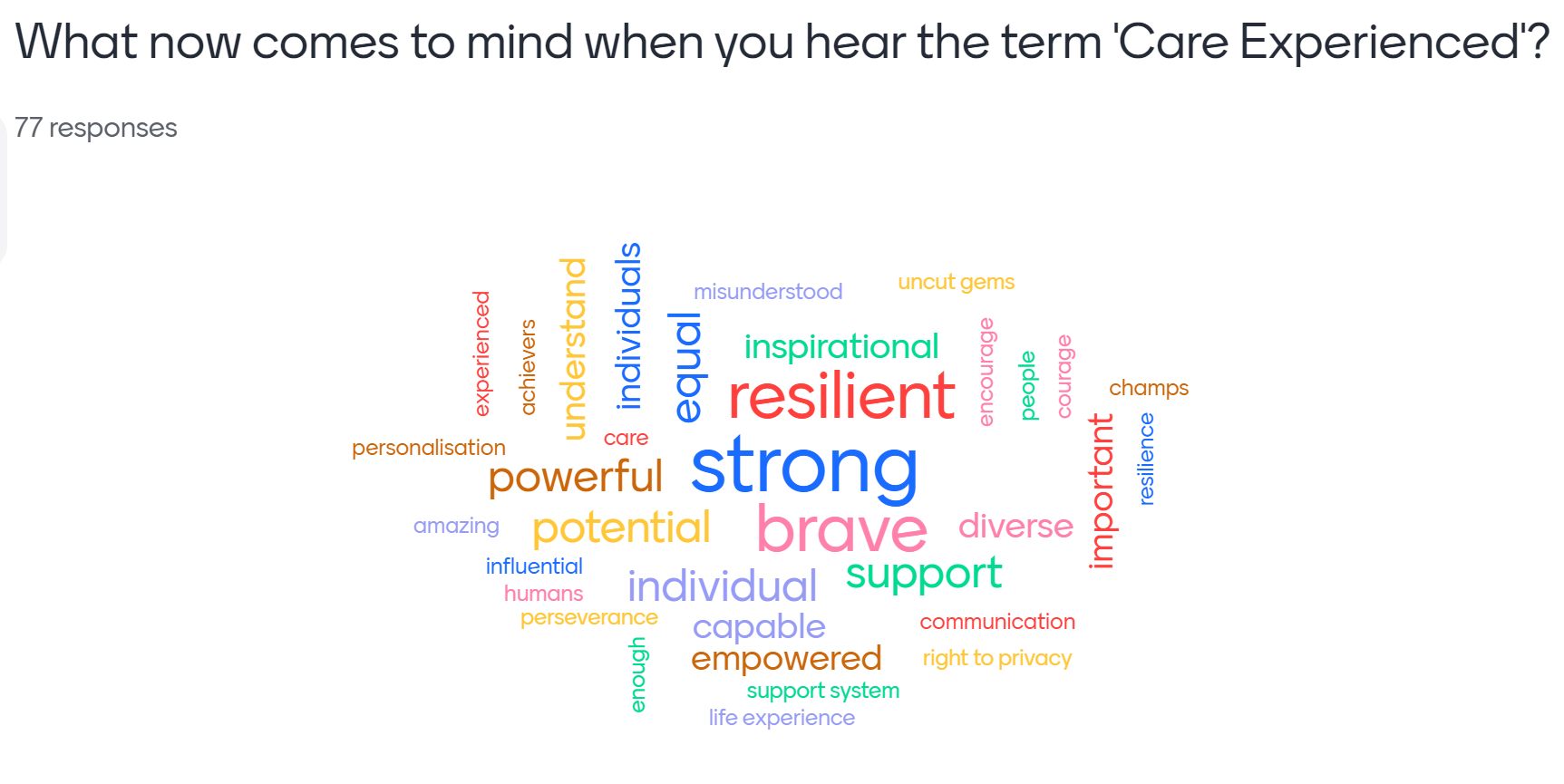

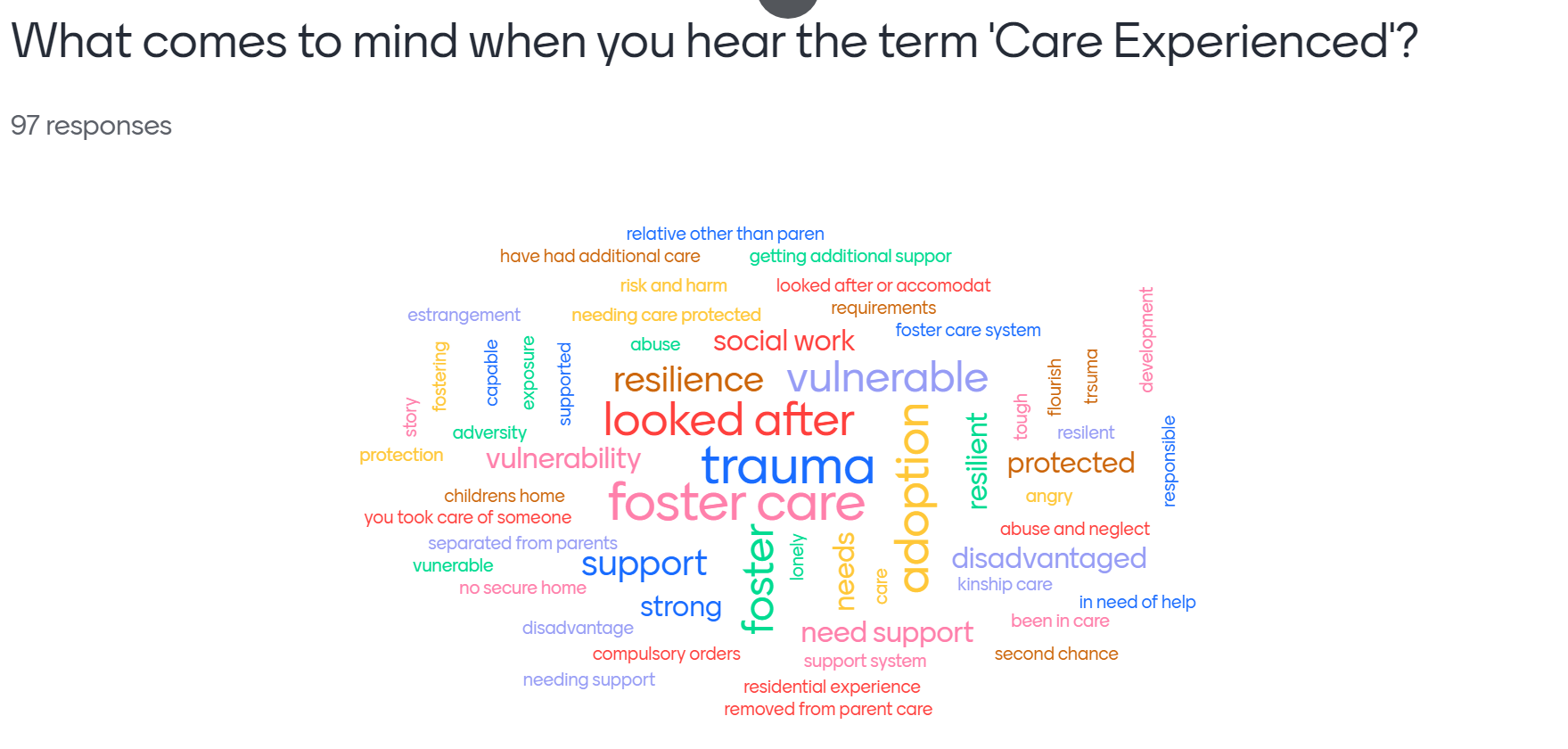

In order to measure the impact of our talk we started our talk by inviting the students to complete a Mentimeter question: what comes to mind when you hear the term care experienced? The students responses demonstrated a rather stereotypical image of a care experienced young person, with words such as ‘trauma’, ‘vulnerable’, ‘disadvantaged’, and ‘in need of help’. Following our talk, we posed the same question to assess whether our message had been received. The change in responses was encouragingly stark, with words such as ‘misunderstood’, ‘uncut gems’, ‘potential’, and ‘individual’.

We would like teachers to continually reflect on their practice in relation to the themes we identified:

- Privacy

- Pastoral support

- Stigma

- High expectation

- Behaviour

- Labelling

Due to the apparent success of our classes, it shows us that we have the ability to make real change in the system. We just have to use our voice, because it is our lives that are being impacted and if we don’t speak out no one will.”

We asked the students what comes to mind when they hear the term care experienced before, and then at the end of the talk and this is what they had to say: